James Chrismer of the Sheet Metal Workers Local 36 worked just one day on the Arch, perfecting expansion joints. Moriarty was paid $2.48 an hour for his work, but he said, “$10 was a huge amount of money back then.” Moriarty had to trudge up 1,076 steps, built section by section as the structure gained height. Louis Arch take an elevator to the top, traveling 340 feet per minute during a five-minute ride. “I was young then, so I took off, ran to the top and got to watch the last section placed.” “My boss bet me $10 that I couldn’t run up the steps to the top,” Moriarty said. Mike Moriarty, now retired from Heat and Frost Insulators Local 1, was the youngest guy on the job – just 15 years old and working on a summer permit – when the Arch was built.Īt the time, Moriarty said, it was “just a job” for him he dreamed he was making history.īut he liked the work – enough to stay in the trade for 40 years. MAKING HISTORY HISTORY MAKERS: Union tradesmen who worked on the construction of the Gateway Arch shared their stories with visitors to the monument during an event on Nov. “I think we’re the only brothers who worked on the Arch,” Hepburn said.

Hepburn’s brother, Bill, another former IBEW Local 1 business representative, also worked on the job. We’d walk 500 feet of steps just to get where we needed to be.” Just getting to the location of where you could work was something. Everything you did kept going up and turning. “A lot of the guys got motion sickness because as the Arch went up the clouds moved overhead giving the feeling of movement inside the close quarters of the steel triangles. “Working on the Arch wasn’t for everyone,” he said.

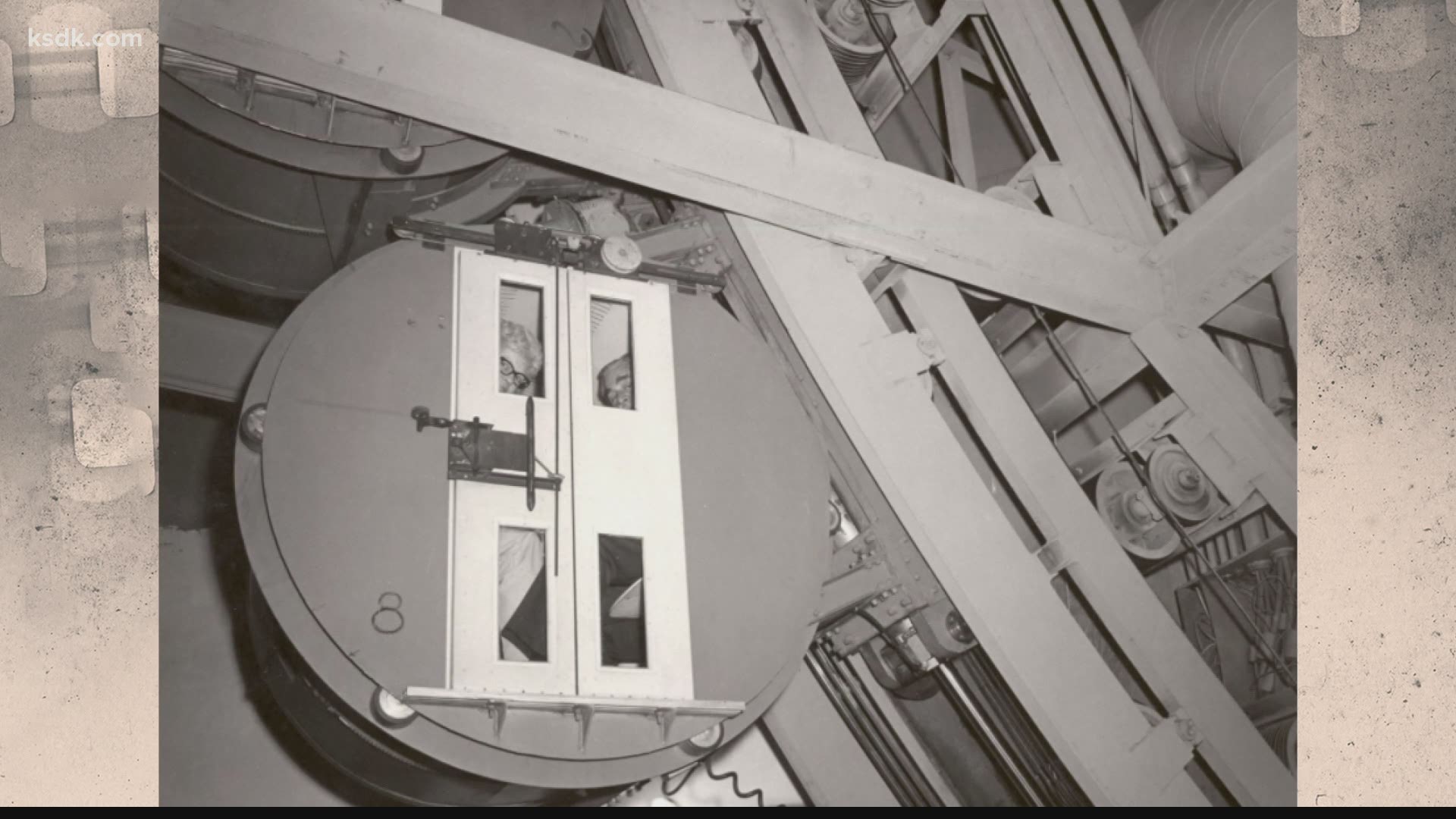

ARCH ST LOUIS ELEVATOR PLUS

When he was working on the Arch, Hepburn was a second-year apprentice making $1.75 per hour plus benefits. Russia’s Red Square used to be ahead of it, Hepburn said, but only because the Communist government required residents to visit. “At the time, I thought it was a heck of a waste of money, but it’s probably one of the most visited monuments in the world,” said Hepburn. Larry “Butch” Hepburn, former organizer/business representative with the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local 1, worked on the Arch for about two and one-half years running wires for the Arch’s interior lighting and for later installation of the elevators. Its inner and outer steel skins, joined to form a composite structure, give it strength to survive an earthquake and permanence to defeat hurricane force winds up to 150 mph. The double-walled, triangular sections placed one on top of another, then welded inside and out the complex engineering design and construction hidden from view became a sparkling stainless steel monument to the men who built it and to the city’s significance as the Gateway to the West.

2 about a dozen retired union tradesmen sat outside of the Museum of Westward Expansion talking with visitors who wanted autographs and a first-hand brush with the men who built the Gateway Arch.Īt its 49 th anniversary, the Arch has been proven by the test of time.

Louis – They didn’t consider themselves artists or extraordinary craftsmen, but on Nov. 28, 1965, when the final piece, the keystone, was set in place. FINAL PIECE: A model in the Museum of Westward Expansion beneath the Gateway Arch shows the topping out ceremony on Oct.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)